Notes

Chapter I: Perpetual Sunshine

1.

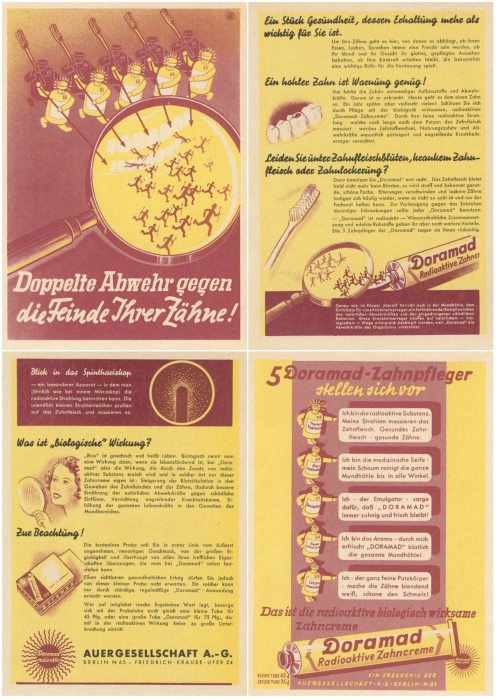

‘charged with new life energy’ … ‘blindingly white’, From an advertising leaflet for Doramad toothpaste, below, undated. The slogan reads: Double Defense against the Enemies of your Teeth!

festival of joy and peace: Joseph Goebbels, quoted in Oliver Hilmes, Berlin 1936: Sixteen Days in August, trans. Jefferson Chase (Bodley Head, 2018), p. 74. Hilmes’ book is a brilliantly immersive, non-academic account of the Nazi Olympics.

'perpetual sunshine': Advertising slogan for Radithor, triple-distilled radioactive water, circa 1928. The American industrialist and golfer Eben Byers drank himself to death in 1932 with three bottles of Radithor a day. The Wall Street Journal’s headline commemorating his passing was ‘The Radium Water Worked Fine Until His Jaw Came Off’.

Chapter II: Super Lost

1.

hyperinflation: In October 1923, Siegfried and his colleagues employed a lookout man to stand at Oranienburg station every Friday. His job was to watch for a man arriving from Berlin with a backpack full of cash. At first sighting, the lookout man ran to the laboratory to tell Siegfried, who, in turn, ran to the bookkeepers’ office where the backpack was emptied and wages handed out in bales of million-mark notes. Siegfried then immediately dashed home, passing his wages to Anna, their housekeeper, who ran to the grocer’s on Bernauer Strasse, being sure to reach the till before the shopkeeper’s phone rang at 3 p.m. The caller would announce the new rates, at which point the money in her hand could lose half its value. In Berlin, meanwhile, tourists could eat fillet steak every night and sleep at the Hotel Kaiserhof for less than a dollar a day.

extraordinarily favourable: Report on Karl Quasebart by Ernst Busemann, 18 September 1933 (IW 24.4./4, Corporate Archives of Evonik Industries AG).

Fritz Haber: Both of Siegfried’s bosses in Oranienburg, Karl Quasebart and Hermann Engelhard, had worked closely with Haber. Quasebart was one of the scientists aboard the Meteor, a ship that sailed all over the Atlantic in 1927 and 1928, collecting thousands of water samples as part of Haber’s doomed project to extract gold from seawater as a way to pay the German war debt. Haber supervised Engelhard’s doctorate on the same subject: how to exploit the ocean as a ‘gold mine’.

‘Nothing was moving and nothing was alive…’: From the diary of Willi Seibert, May 1915, after the second battle at Ypres. The full quotation is: ‘Nothing was moving and nothing was alive. All the animals had come out of their holes to die. The smell of gas hung in the air, clinging to the few bushes that were still standing. When we got to the French lines the trenches were empty, but in a half-mile the bodies of French soldiers were everywhere. It was terrible. Then we saw the British. We could clearly see from their scratched faces and necks that they were desperately trying to get some air.’

‘No author has ever expressed her contempt for the audience in such flagrant fashion’: Heywood Broun, New York World, 28 May 1922. Broun later changed his opinion, writing in 1931: ‘I am willing to admit that it was an excellent and tonic thing that the general public succeeded in reversing a critical opinion which was almost unanimous.’

‘America’s favorite comedy. God forbid’: Robert Benchley, Life magazine, 9 August 1923. This was just one of many of Benchley’s attacks on Anne Nichols’ play during its record-breaking run on Broadway. An edited version of Benchley’s review was used in the lobby of the theatre. A poster read: ‘America’s favorite comedy’. In another of his mini-reviews, he wrote: ‘People laugh at this every night, which explains why a democracy can never be a success.’

‘a plague-stricken area, where men and women, haggard from sleeplessness …’: The Times, 23 May 1928, p. 16. The full headline was: ‘The Poison Gas Disaster. Eleven deaths. Hamburg a Prey to Fear’.

4.

‘uncosy’: The change in Oranienburg’s atmosphere after 1933 was also indicated by the experience of Dr Schwartze, a Nazi Party member who lived at 34b Bernauer Strasse, three blocks north of Siegfried’s apartment. On a Friday morning in July 1935, he received a letter – a ‘formal caution’ – from a Nazi official informing him that he had been spotted buying his meat from Bach Brothers, a Jewish-owned business. Schwartze wrote back that he knew ‘a great number of party members who shop with Jewish companies’ and that he would continue to buy his shirts from Hoffmans in Berlin, his ‘undergarments and linens from Grünfeld’ and his meat from Bach Brothers – all of whom he’d frequented ‘for the last forty years’. He ended the letter by noting that – on account of his having never bothered to collect his membership card, nor having ever sworn allegiance to the Führer – it should be simple enough to revoke his party membership. The Nazi leadership decided to make an example of him and published his letter in the local pro-Nazi newspaper, the same paper that had told its readers: ‘We Germans are and will remain anti-Semites, and Oranienburg is willing to become and remain free of Jews!’ Three days after the letter was published, Dr Schwartze lay in bed with a bleeding stomach and intestinal disorders, listening to the hundreds of Nazi supporters that were gathered outside his apartment, chanting for him – the ‘Jew-slave’, the ‘traitor to the people’ – to come outside. When he did not open his door, the police kicked it down and put him in ‘protective custody’. As they walked him across town to the police station, he was spat on at least forty times by a group of young people wearing the uniform of the Hitler Youth. He arrived at the station bleeding from his mouth and nose.

'unconditional obedience'. From July 1935, all military units were required to swear loyalty to Hitler: ‘I swear by God this holy oath, that I will render to Adolf Hitler, Führer of the German Reich and People, Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, unconditional obedience, and that I am ready, as a brave soldier, to risk my life at any time for this oath.’

7.

'help large sections of the German people to psychologically familiarize themselves with the horrors of chemical warfare …': Olaf Groehler, Der Lautlose Tod (Verlag der Nation, 1987) p. 98.

On Grawitz recommending to Himmler the effectiveness of gas chambers, see Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews (Yale University Press, 2003), p. 873.

the perverted world of the homosexual: Richard Plant, The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War against Homosexuals (Henry Holt, 2011), p. 99.

Chapter III: Orgacid

1.

'production and distribution of chemical products of all kinds, especially Orgacid': ed. Bretislav Friedrich, Dieter Hoffmann, Jürgen Renn et al, One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences (Springer, 2017), p. 300.

'Orgacid was a phantom whose existence even its founders could not seem to remember': Olaf Groehler, Der Lautlose Tod (Verlag der Nation, 1987), p. 113.

IV. Young Republic

1.

‘next to the poison gas laboratory’: Turkish government document confirming the purchase of land for the construction of the Mamak gas mask factory, 19 September 1934 (catalogue number: 030_0_18_01_02_48_62_013, Cumhurbaşkanlığı cumhuriyet arsivi, Ankara).

‘order larger quantities of the chemicals …’: Letter from Siegfried Merzbacher to Professor Karl Quasebart, 10 April 1937 (K 776, Mp. 3, 2009/136/28-67, Jewish Museum, Berlin).

3.

‘a dangerous abscess … that must be operated on decisively’: Hamdi Bey’s 1926 report on the situation in Dersim is reprinted in Reşat Hallı’s Türkiye Cumhuriyetinde Ayaklanmalar (1924–1938) (Genelkurmay Basımevi, Ankara, 1972), p. 375.

‘precipitous valleys and inaccessible mountains … the streets of Ankara’: from Ismet Inönü’s speech to the Turkish Grand National Assembly on 18 September 1937. It was quoted in an article by Abdullah Kiliç and Ayça Örer and serialized in Radikal magazine, 20–24 November 2011. The article was translated into English by Tim Drayton and the full translation is available here: here.

'The water flowed bloody...': witness statement by Hanım Erdoğan, T24, February 4 2015, accessed November 26 2024, https://t24.com.tr/haber/babam-46-sungu-darbesiyle-oldu-ailemden-38-kisi-kursuna-dizildi-bu-suc-alevileri-sevmeyenlerin,285983. Similarly, a soldier who took part in the massacre, Mahmut T, described how 'the Munzur would bleed bright red for two or three days.' His statement is available here: https://manage-rudaw-net.translate.goog/turkish/kurdistan/030520217?_x_tr_sl=tr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp

‘They used poison gas ...’: interview with İhsan Sabri Çağlayangil, T24, November 19 2011, accessed November 12, 2024, https://t24.com.tr/haber/caglayangil-ordu-dersim-kurtlerini-kesti-fare-gibi-zehirledi,182465.

‘I can’t forget the excitement of the first bombardment’: interview with Sabiha Gökcen, Ataturk’s adopted daughter, Milliyet newspaper, 25 November 1956, p. 4.

7.

Dersim History and Culture Centre: Despite immense political pressure and at great personal risk, the members of this organisation have gathered extraordinarily comprehensive documentation of the massacres in Dersim, including hundreds of hours of recorded interviews with both survivors and perpetrators. For more information about their work and the history of Dersim, visit dersim-tertele.com

Chapter V: Your Very Devoted Servant

2.

‘I have known Professor Quasebart for about twenty years …’: Denazification proceedings of Prof. Dr. Ing. Karl Quasebart (C Rep. 031-01-06, Serial No 1028, Landesarchiv, Berlin).

‘horrid tiresome business …’: Frederick Taylor, Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany (Bloomsbury, 2012), p. 312.

‘good idea badly carried out’: Ibid., p. xxxiii.

‘politically unreliable’: Letter from Reinhard Heydrich (Head of Reich Police) to Heinrich Himmler, 6 January 1939 (Betr.: B Nr. V.A.: 301/36, 6.1.1939, SS-HO 5686, Bundesarchiv, Berlin).

Chapter VI: Equanimity

1.

‘a wonderful little spot, a quaint and ceremonious village of puny demigods on stilts’: From a friendly letter Einstein wrote to the queen of Belgium, quoted in Craig Nelson’s excellent The Age of Radiance (Simon & Schuster, 2014), p. 114.

‘the most severe within memory’: The Times, 11 July 1957, p. 10. The full headline was: ‘Persian Villages Turned to Cemeteries. Havoc Wrought by Earthquakes. 10,000 Injured’.

School

‘Hurrah, Germania!’: Ferdinand Freiligrath, English translation in The Age of Bismarck: Documents and Interpretations, ed. Theodore S. Hamerow (Harper & Row, 1973), pp. 96–7.

‘these Jewish lawyers’: Douglas Morris, Justice Imperiled: Max Hirschberg (University of Michigan Press, 2005), p. 268.

‘foamed’: Ibid., p. 264.

‘a certain Narzbacher’: Ibid., p. 18.

Work

‘new kind of light for the investigation of dark places’: Popular Science, November 1910, p. 450.

3.

‘sociopathic personality disturbance’: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 1st edn (American Psychiatric Association, 1952), p. 38.

‘hectic glow’: Henry David Thoreau, quoted in Susan Sontag’s essay ‘Illness as Metaphor’, New York Review of Books, 26 January 1978.

Chapter VII: The Other Side of the Wall

1.

‘handsome, balanced features …’: From a letter to Anna von Gierke, 13 November 1933 (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 568.

2.

‘without fear of social descent or of finding importunate people’: Dennis B. Klein, Jewish Origins of the Psychoanalytic Movement (The University of Chicago Press, 1985), p. 17. This quote comes from a speech given by the president of the Vienna branch of the Independent Order of B’nai B’rith, which, as the name suggests, was a kind of Jewish Freemasons. Elisabeth and Siegfried’s father was a leading member of the Munich branch. The stated goal of the B’nai B’rith was ‘To develop, to raise and to ennoble the spiritual and moral character of the Jews generally and of the members specifically; to enforce the most pure principles of the humanity, honour and patriotism among them; … to support science and arts; to ease the misery of the poor and needy; to care for the sick; to protect widows and orphans.’

3.

‘not trivial, but … of the deepest meaning …’: Friedrich Fröbel, Die Menschenerziehung (Keilhau, 1826), p. 69.

‘little garden in the sunshine’: Anonymous poem written for the kindergarten, circa 1904 (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 452.

‘hygiene, which was foreign to them’: Hans Lamm (ed.), Von Juden in Munchen (Ner-Tamid-Verlag, 1958), p. 75.

‘children moved in beaming’: Report on the children’s home by Elisabeth Kitzinger (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 516.

4.

‘To me at least it was quite obvious that there was absolutely no future for them’: Ernst Kitzinger and Richard Candida Smith, Ernst Kitzinger: Style and Its Meaning in Early Medieval Art (The J. Paul Getty Trust, 1997), p. 9. In this interview, Ernst also tells the story of when he and his mother, Elisabeth Kitzinger, had tea with Hitler in Munich’s Café Heck. One evening in 1933 or 1934, they came out of the cinema and watched a line of sleek black cars pass them on Odeonsplatz and, knowing this could only be one person, they decided to follow the new chancellor into one of his favourite cafés. Hitler was sitting with his colleagues at the far end of the long room, his back to the wall, a bodyguard watching from across the aisle. Elisabeth and her son were not allowed to take the nearest table but got close enough to Hitler to be ‘struck by the dainty way he held his cup’. Ernst noted ‘how unimpressive he looked … rather slight, with a sallow complexion. Even the famous diagonal sweep of hair was not as dramatic as in the photograph.’ They could not marry his physical self with the outsized damage he was doing to their lives. As they watched him quietly drink and chat, Ernst felt a rising need to scream, to shatter the veneer of good manners, an instinct that was matched by the simultaneous understanding that, if he did so, the consequences would be immediate. In Café Heck – as in the rest of their lives – they recognized that there were only two options: repress your anger, or pay up and leave. Two years later, Ernst had chosen the latter and was on a swaying boat in the English Channel, successfully lying to an immigration officer about his plans for a quick research trip to the British Library – a visit that would last almost a decade.

‘the Nazis had fallen in love with the house on Antonienstrasse’: Letter from Elisabeth Kitzinger in Tel Aviv to Lilli and Siegfried in Ankara, 14 April 1939 (2009/393/118-128, K 778, Mpp. 4-5, Jewish Museum, Berlin).

‘like an iron belt’: Ibid.

‘in a condition that can hardly be described …’: Ibid.

‘I don’t know whether I can come to you again …’: Ibid.

‘Physical separation is only an illusion …’: Letter from Alice Bendix to Elisabeth Kitzinger, 28 May 1939 (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 691.

‘How much I miss your living, breathing proximity …’: Letter from Alice Bendix to Elisabeth Kitzinger, 9 February 1941 (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 731.

‘being beautifully decorated’: Martin Ruch, ‘Inzwischen sind wir nun besternt worden’: Das Tagebuch der Esther Cohn und die Kinder vom Münchner Antonienheim (KulturAgentur, 2006), p. 94.

‘I don’t feel anything from the hard bed’: Ibid., p. 89.

‘indescribable, hopeless screaming’: Interview with Ernst Grube as part of the art installation Federbetten nur für Kinder, CultureClouds e.V (2021). The full quotation is: ‘For me, Milbertshofen was the worst place of that time. Every day, and also at night, employees of the Secret State Police came. They chased Jewish people – for whatever reason – through the camp, tortured them and locked them in the old boiler house that stood in the middle of the camp. There are many things that you forget. Time heals all wounds, they say. Not here. This indescribable, hopeless screaming rings in my ears. It’s still there, as if it were last week.’ For more about Ernst, see https://www.stories.nsdoku.de/ernst-grube

‘Better accommodation since July …’: Letter from Alice Bendix to Elisabeth Kitzinger, 23 August 1942 (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 672.

5.

‘calm and collected and of an almost cheerful, optimistic disposition’: Letter from Carola Castan to Elisabeth Kitzinger, 17 August 1947 (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 743.

6.

‘has proved that the energy of a real person often achieves more …’: Rabbi Leo Baerwald in Aufbau magazine, 21 April 1961 (Ernst Kitzinger Collection, Leo Baeck Institute Archives), p. 642.

‘it did not seem appropriate to us …’: E. G. Lowenthal (ed.), Bewährung im Untergang (Council of Jews from Germany, 1965), p. 10.

Select Bibliography

Richard J. Evans, The Coming of The Third Reich (Penguin, 2004). The first of Evans’ fresh and vivid trilogy about the Nazis. He makes use of the many revelatory sources – such as Goebbels’ diaries – that have only recently become available.

Peter Hayes, From Cooperation to Complicity: Degussa in the Third Reich (Cambridge University Press, 2004). A balanced and deeply researched academic case study of military-industrial complicity in the Holocaust.

Sema Kaygusuz, Every Fire You Tend, trans. Nicholas Glastonbury (Tilted Axis Press, 2019). A lyrical novel in which the events of 1938 in Dersim echo through the life of an unnamed protagonist.

Bettyan Kevles, Naked to the Bone (Rutgers University Press, 1997). A fascinating and wide-ranging social history of X-rays, radiation and medical imaging

Benjamin Labatut, When We Cease to Understand the World (Pushkin Press, 2020). A ‘non-fiction novel’ that is brilliant and terrifying, particularly for its first chapter, which gives an account of the moral complexity of the career of Fritz Haber.

Nilüfer Saltik and Cemal Tas (eds), Tertele (Kalan, 2016). A stunning trilingual book, combining music, photography and historical documentation, that takes a humane, many-sided approach to remembering the Dersim massacres of 1938.

Frederick Taylor, Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany (Bloomsbury, 2012). A smart and readable account of the Allies’ attempts to denazify Germany.